Waddesdon's lost glasshouses

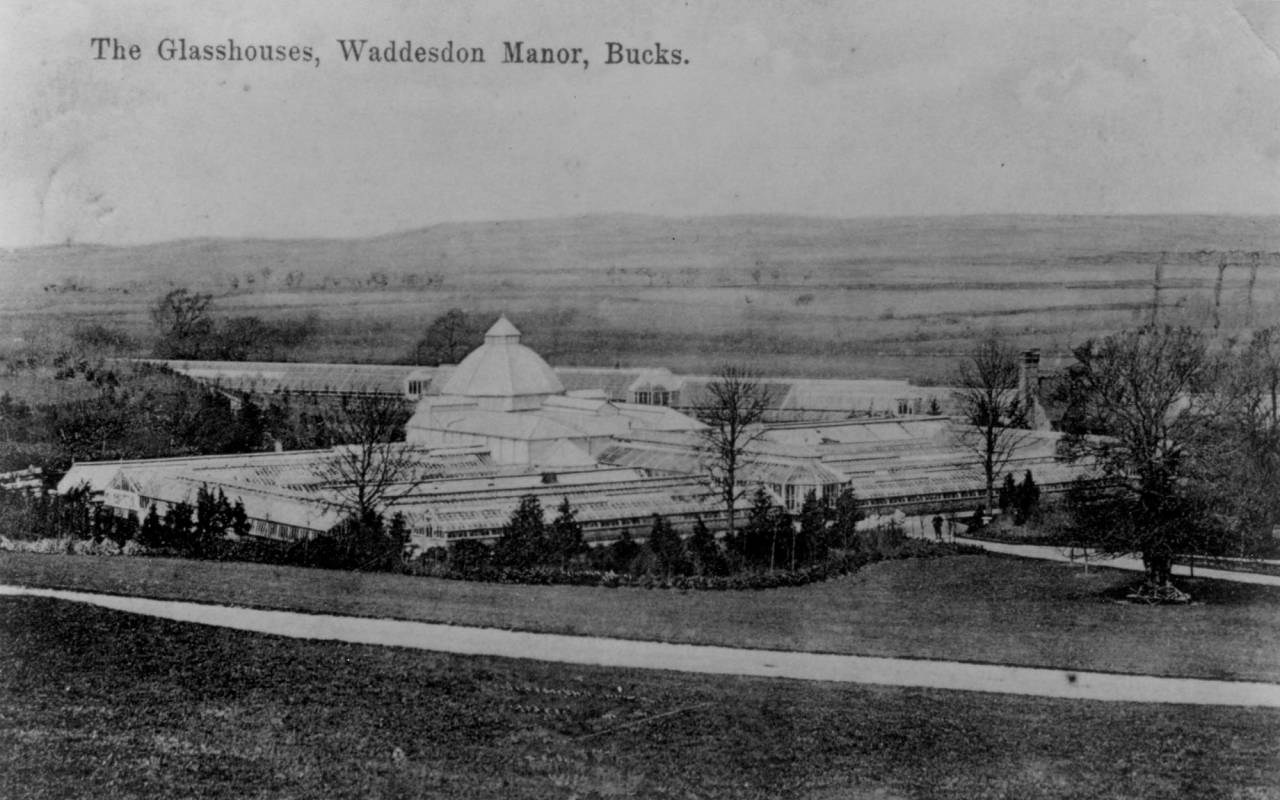

An important part of Baron Ferdinand’s ‘Saturday to Monday’ parties would have been a visit to the glasshouses. Here we take a look back at Waddesdon's lost glasshouses, that were demolished in the 1970s.

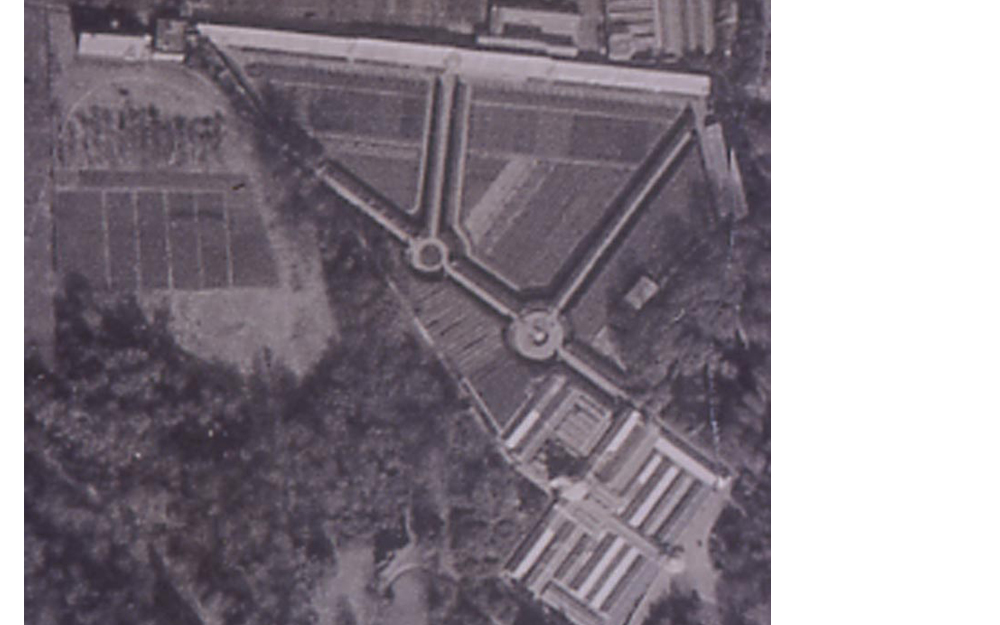

The glasshouses, built by the Victorian manufacturer R. Halliday & Co, were situated below the stable block where the sloping ground levels out.

The main glasshouse, known as ‘Top Glass’, was made up of fifty different compartments, and the centre piece was a large domed glasshouse which was landscaped with rockwork and an underground cavern, and was planted with palm trees and ferns.

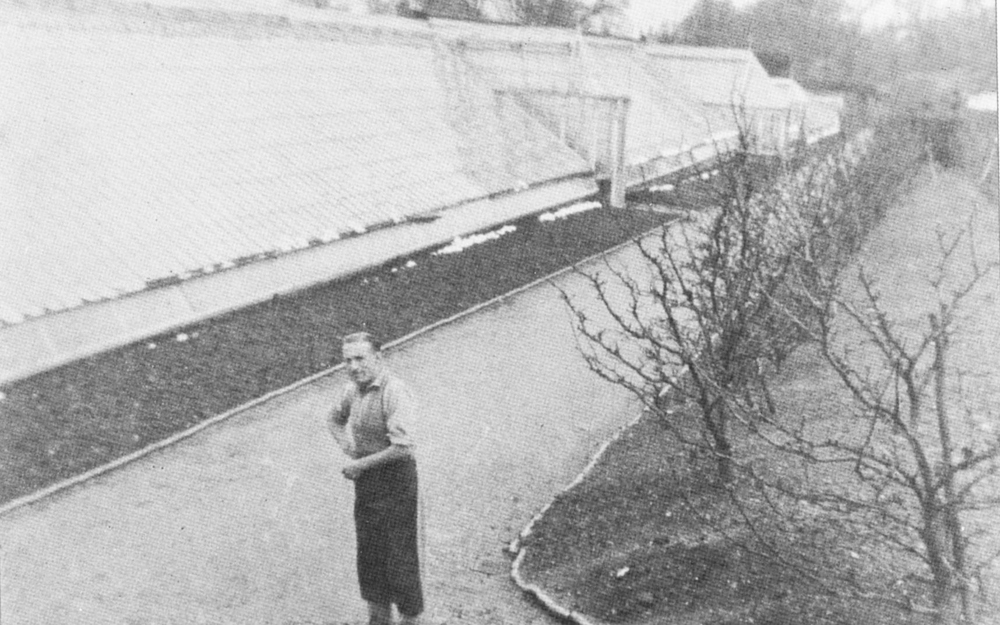

Beyond this was a huge, 400 ft. long wall with a ‘lean-to’ glasshouse, the so-called Fruit Range. This long glasshouse was divided into nine sections, devoted to the production of fruit including: cherries, figs, grapes, peaches, vines and strawberries.

Like everything else at Waddesdon, the fruit was grown to the very highest standard. Baron Ferdinand’s sister, Miss Alice, who inherited the property upon his death in 1898, regularly gave detailed instruction to her head gardener George F Johnson.

In a letter dated December 1906 she mentioned that ‘Plums can be watered with chalky water, but no other fruit trees and you had better find out before you use much Chiltern water for the pot plums whether it contains anything injurious to plum trees’.

Miss Alice even required Johnson to change the soil as ‘[all] fruit grown for my table ought to be grown in the right soil. The pure Waddesdon soil, even the best Waddesdon loam, gives an acid taste to fruit and makes vegetables hard’.

Beyond the wall of the Fruit Range lay a large kitchen garden, away from the eyes of the visitor, for the cultivation of yet more soft fruit and a wide range of vegetables. During WWI the general food shortages meant some of the Waddesdon produce was, for the first time, sold to the wider public. From then onwards the glasshouses and kitchen gardens developed into a kind of market garden venture, supplying local businesses as well as Covent Garden market.

The operation was scaled down after the death of James de Rothschild in 1957, when his widow Dorothy moved out of Waddesdon Manor to the neighbouring Eythrope Pavilion, taking some of the glasshouse and kitchen garden staff with her.

Though the Waddesdon glasshouses fell into disrepair and were finally pulled down in the 1970s, the kitchen garden continued to function as a garden centre until a few years ago.

Today, even though this important aspect of Waddesdon’s garden has disappeared, it is possible to get a glimpse of it by visiting Eythrope’s walled garden where you can observe fruit and vegetables grown to the very highest Rothschild standard. The Waddesdon Estate also continues to farm commercially and care for the neighbouring countryside. Over 3,000 acres of land are farmed ‘in-hand’ alongside five tenant farms producing both crops and livestock. Many crops go into making local produce including fruit infused gins, barley for brewing, and pollen rich echium for honey. Local produce, including sparkling wines, gins, ales, cheeses, chutneys and preserves, are created exclusively for Waddesdon and are available on the online shop.

Written by Garden Historian, Sophie Piebenga