Zoology and zebras: Walter Rothschild and his museum

We invited PhD student and Walter Rothschild expert, Elle Larsson, to share her knowledge on the man behind the spectacular collection of specimens housed in the Natural History Museum at Tring.

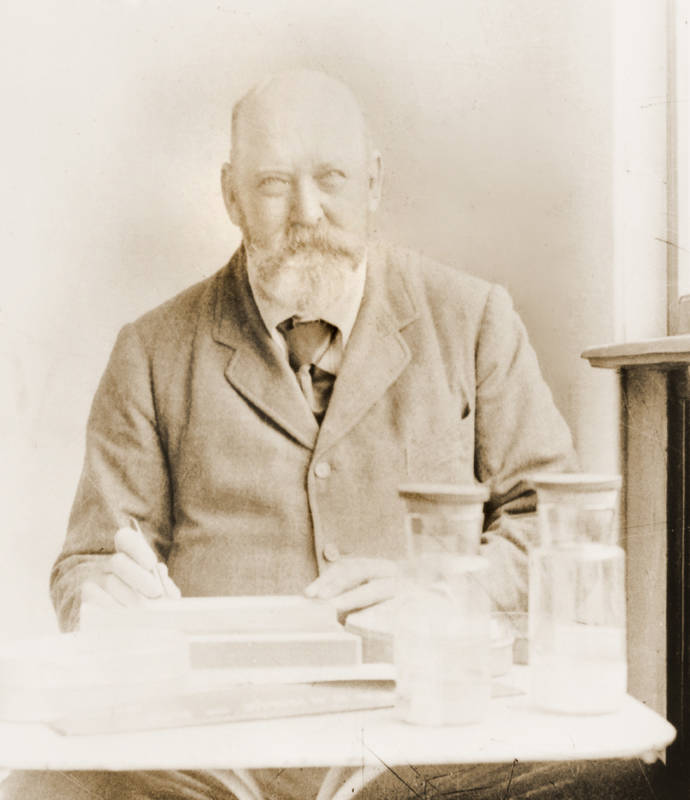

When people hear the name Rothschild the first connection they are likely to make is with banking, and if not banking than perhaps lavish country houses and collections of exquisite art works, pieces of furniture and jewels. But perhaps lesser known is the affiliation members of the Rothschild family have with science, animals and natural history. Waddesdon’s Baron Ferdinand (1839-1898), for example, had his own small aviary which bustled with exotic birds (and which as a visitor you can still see today); Maurice Rothschild (1881-1957) undertook an expedition to East Africa between 1904-05 and produced publications on giraffe and okapi; while Ferdinand’s nephew Charles (1877-1923) and great niece Miriam (1908-2005), were leading experts on fleas and contributed significantly to the nature conservation movement. However, the most famous naturalist of the Rothschild family has to have been Walter Rothschild (1868-1937), 2nd Baron Rothschild, Ferdinand’s nephew, and the inspiration for the current Creatures & Creations exhibition at Waddesdon.

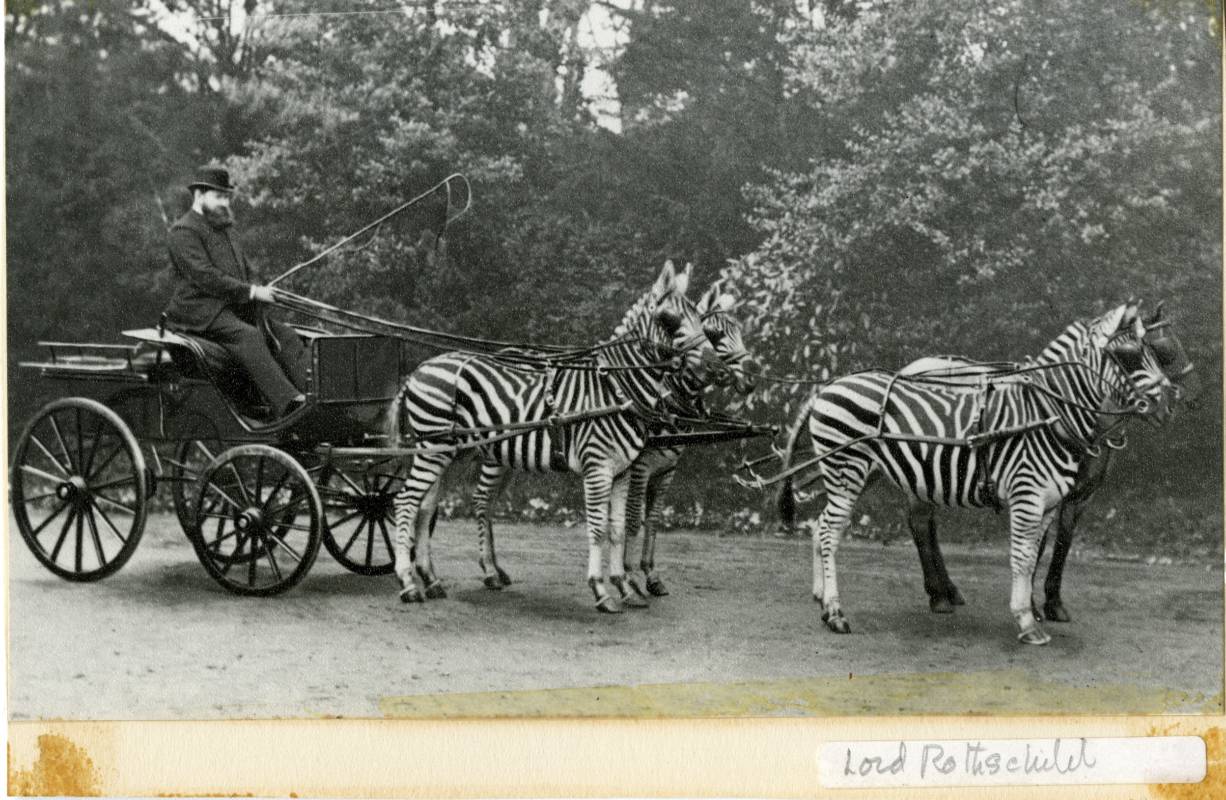

There are three things that people tend to know about Walter Rothschild– that he trained three zebras to pull a carriage, that he was obsessed with the classification of cassowaries and that he was once photographed sat upon a giant tortoise. These were eccentric acts which capture interest as much now as they did then, and yet, they are some of the least interesting acts when the extent of Walter’s involvement in late-nineteenth early-twentieth century natural history is considered.

It had been expected that Walter would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a partner in N.M. Rothschilds & Sons, however, banking was not to prove his forte. Instead Walter became an outstanding naturalist who established the largest private collection of natural history specimens the world had ever seen, and, together with his curators, Ernst Hartert and Karl Jordan, contributed significantly to the study of animal species and their distribution, describing over 5,000 new species and publishing some 1,200 books and articles based on taxonomic work.

However, Walter was operating at a time when ‘professional’ scientists were emerging as the dominant forces in the field of science and wealthy, amateur, private collectors like Walter were less commonplace than they had once been. That he developed a research collection, public museum, produced his own journal, developed an extensive network of contacts through which he acquired specimens and knowledge and, gained a reputation as a zoologist amongst his contemporaries, is therefore particularly significant when considering natural history during this period.

And this is what the exhibition Creatures & Creations has captured. The 14 species which have inspired the exhibition all share the name Rothschildi and were named after Walter by other prominent zoologists of the period. For instance, in 1912 German naturalist and ornithologist Erwin Stresemann (1889-1972) described for the first time the Bali Starling, or Leucopsar rothschildi, naming it after Walter. This was nod of acceptance and an acknowledgment of the valuable contribution Walter had made to zoology.

In taking inspiration from these species, Platon H and Mary Katrantzou have begun to show to a modern audience that while fascinating, Walter’s unusual acts involving zebra and tortoises were just a small part of a much, much larger story.

Elle Larsson, 27 September 2017

@Elle_Larsson