Waddesdon letters: war and weather

Samuel Johnson once said 'In a man’s letters his soul lies naked' and it's certainly the case that a person's letters often tell you more about their thoughts, feelings and opinions than anything else does.

We have very few letters either written or received by Miss Alice de Rothschild but we do have a series of over 100 hundred letters written to her Head Gardener, George Frederick Johnson. These letters give a fascinating picture of Alice’s interests and thoughts about various subjects. They show her sense of care and responsibility for all those working for her and relying on Waddesdon and they show her sense of family and identity when the First World war threatened everything she had known.

Johnson had started his career as a garden boy at Waddesdon at the end of the nineteenth century before going to work for one of Alice’s cousins on the continent. When her Head Gardener retired in 1905 she wrote to Johnson to offer him the job:

‘I do not like changes and as I know you well, I offer you the place of head gardener here – a furnished house, coals, milk, potatoes and vegetables -, a horse and cart at your disposal, the doctor and medicines gratis for yourself and for your household.’

This was the first in a long series of letters that cover the period to Alice’s death in 1922. The letters show a relationship that grows over the years and with familiarity. Alice writes to Johnson on a plethora of subjects not confining herself to instructions about the garden and the distribution of garden produce but also commenting on the health of his staff and family, on the weather, the political situation and of course the First World War.

Alice’s letters contain a level of detail and knowledge that might be surprising – she certainly didn’t leave all the decisions to Johnson but suggested improvements and changes to everything from planting to the arrangements for the under gardeners in the bothy:

‘Each cupboard ought to have a different lock and the key ought to be numbered according to the rooms, from No 1 to 11, and I think I remember that there are 11 bed rooms in the bothy. Each room ought to contain – a bed, a table and shelf, a wash hand stand; but all this can be done after my return to England; as previously arranged, no one is to sleep in the bothy before the first week in Sept. at the earliest.’

She also writes to Johnson about advancements in the technical side of gardening and caring for the plants in the flower garden but also the fruit cages and glasshouses. Whether is the best use of artificial fertilisers as advised by her gardener at her estate in Grasse:

‘The engrais fennel he uses only for the Petunias and Gloxinias; proportions one tea spoonful to three litres of water. Use this mixture four months before the gloxinias flower about once a week. The blood in powder he uses for the Callas half a kilo of the powder mixed in 100 litres of water, that in the proportion and he waters the callas with it once a week four months before they flower, until they have done flowering. He uses the blood powder also for roses. The nitrate of soda he uses for turf and for herbaceous flowers.

I do not see why we should not have as good gloxinias, callas and petunias at Waddesdon as they are cutting[s] grown under glass, as Tabard grows here.’

Or a warning not to expose the gardens at Waddesdon to a new disease, probably American Gooseberry Mildew, being brought over from America:

‘Be careful not to buy any gooseberry, or blackcurrant bushes, in order to prevent the introduction of the terrible new American disease – could you propagate these bushes, from our own best varieties, for use when our present bushes are exhausted?’

She also writes to Johnson of more personal matters showing an interest in his welfare and the welfare of his family and staff:

‘I congratulate you on the birth of your daughter and hope that your wife’s condition will continue to be satisfactory. I hear that Miss Chinnery intends going to Bournemouth for Christmas. I have told Sims to send her a turkey and Mrs Scott to make her a cake.’

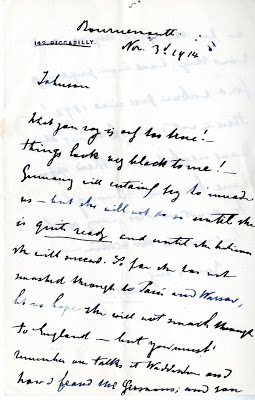

Her letters for the period of the First World War are a strange mix of comments on where to send grapes and potatoes and her thoughts on the political situation:

‘What you say is only too true! – things look very black to me! – Germany will certainly try to invade us – but she will not do so until she is quite ready and until she believes she will succeed.’

She is also concerned about how Johnson will manage as conscription starts in 1916 and he loses more men to the army and has to maintain standards with a much reduced workforce:

‘How will you manage when your men leave you? Can you find some to replace a few of them? What terrible times we are living in to be sure and how and when will it all end?’

Her letters also comment frequently on the fortunes of the Waddesdon men who are fighting – passing on her congratulations to those who had won the Military medal and her sympathy and best wishes to those whose sons would not be returning home.

Finally a theme that is sustained throughout the whole period are her comments on the weather and how that might affect life whether through delays to the postal service or problems in the gardens:

‘I hope the weather will improve before you leave on Saturday, as the gales on the north coasts of France have been very rough lately. It is dry, cold and fine here. This morning we had one degree below zero at Consulat and five below zero at the Pavilion!’

By Catherine Taylor, Head Archivist.