Paulet’s pendant: dragon slayer or maenad?

While Power & Portraiture: Painting at the Court of Elizabeth I, a special display centred on two splendid portraits by Nicholas Hilliard, continues until 29 October, curator Dr Juliet Carey’s research sheds light on the pendant worn by Sir Amias Paulet, Elizabeth I’s ambassador to France from 1576-9.

In the exhibition, visitors will learn about the scientific discoveries that prove that the two portraits were painted by Hilliard and how these oil paintings on panel transform our understanding of an artist famous for his miniatures. However, gallery interpretation can encapsulate only a fraction of what we know about the exhibits and some research bears fruit only after the labels and leaflets are written. One thing that frustrated me when the display opened to the public was that I had not found out much about Paulet’s pendant.

There is wonderful jewellery in the Elizabethan paintings at Waddesdon. Elizabeth I wears a phoenix jewel in one portrait and a pelican jewel in the other. Her clothes are covered in jewels, including hundreds of pearls and enormous, transparent diamonds. Her male courtiers show off precious metals and precious stones in buttons, hat decorations, buckles, swords and purses. All wear medallions on elaborate gold chains.

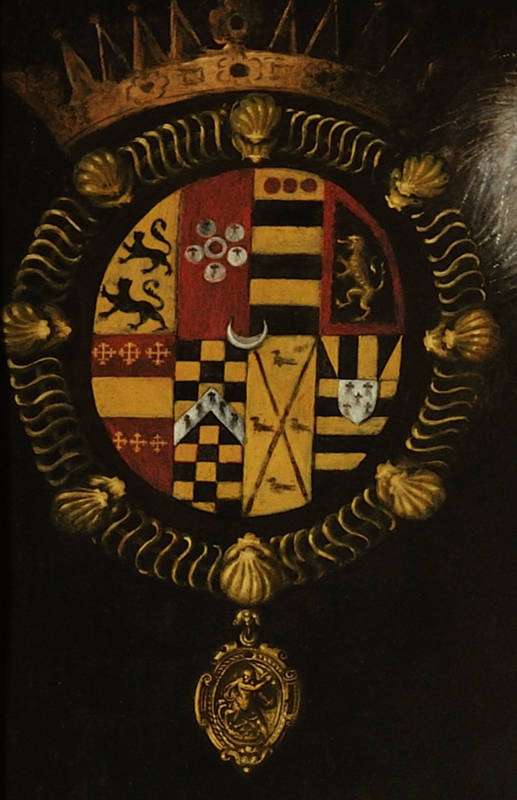

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk have the Lesser George, which depicts St. George killing the dragon surrounded by the motto of the Order of the Garter, the highest English order of chivalry.

As well as the Order of the Garter, both men were members of the French Order of Saint Michael, an honour conferred on them by Charles IX in 1566 as a compliment to Queen Elizabeth, who, as a woman, could not be admitted to this military order. Dudley was so proud of this that he had his arms encircled by the Order of St Michael added in the top left corner of his portrait, after the painting was finished. You can see Saint Michael killing the dragon in the medallion.

When I first saw the Hilliard portrait of Sir Amias Paulet, I jumped to the conclusion that his medallion also depicts Saint Michael killing the dragon.

I interpreted the figure as a standing man, facing towards the viewer and wrestling with a serpent-like creature, although I couldn’t read it clearly and was therefore troubled by the vague way that Hilliard had delineated it as he – trained as a goldsmith and the son of a goldsmith – described other, much smaller details of jewellery so clearly. With the help of others, I discovered that my initial, lazy conclusion was wrong.

Although one French king admitted Robert Dudley and Thomas Howard to the Order of Saint Michael, Tracey Sowerby, an historian with a particular interest in the cultural history of Tudor diplomacy, pointed out that it was unthinkable that his successor, Henri III, who was king at the time Hilliard painted Paulet, would have honoured this aggressively Protestant sitter, who Henri regarded as a heretic. This prompted me to double-check and of course there is no record of Paulet being admitted to the order. But I still thought the figure was a man, facing us and wrestling something snake-like. Maybe Hercules.

Then Avery Schroeder, an intern at Waddesdon from the Bard Graduate Center looked closely at the pendant in the portrait. She made a drawing of it, to help her look, and showed me that I had been reading the figure incorrectly. The figure is a woman, facing the other way entirely, with her head thrown back, her left arm stretched out, her right arm bent at the elbow, with long hair and fluttering drapery. She is dancing with a combination of grace and abandon, like an antique maenad or bacchante.

The possibility that Paulet might be wearing a classical or Renaissance cameo led me to the think about the taste for such works of art in Elizabethan England including, for example, the Hunsdon Onyx, on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Link to image of the Hunsdon Onyx >

Centred on another sexy, classicizing female subject, this beautiful gem shows Perseus about to rescue Andromeda from the sea monster. It was made by the Milanese mannerist gem engraver Alessandro Masnago (fl. C. 1575-1612) and offers an intriguing comparison with Paulet’s maenad. Like the more famous Drake Jewel, which, significantly in this context, Sir Francis Drake wears in the portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts II (1561/2-1636) (1591, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich), the Hunsdon Onyx is reputed to have been presented by Elizabeth I to a kinsman-courtier, although there is no conclusive evidence for this.

Might Paulet’s jewel have been a gift from the queen? Or did he acquire it in France (François Ier had brought Italian gem engravers to France and Catherine de Medici brought with her an important collection of gems)? Wherever it came from – and we may never know – it adds a highly sophisticated, cosmopolitan element to his visual self-fashioning, connecting him to the trans-European cultures of gem cutting and gem collecting.

The gem may even still exist. Richard Edgcumbe, Senior Curator at the V&A, told me that the white oval that surrounds the figure on Paulet’s gem suggests that it is carved from layered agate and suggested I contact Claudia Wagner, Senior Researcher on the Beazley Archive Gem Programme. It turned out that Dr. Wagner had been thinking about maenads recently too and replied immediately. Her response made Hilliard’s painted representation excitingly real. Not only did she tell me that its unusually large size and raised frame confirmed that it was a Renaissance gem rather than an ancient one, she also sent a photograph of it. Or, more correctly, a photograph of a cast of what is almost certainly the same object, made when the cameo was in the collection of Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquis of Rockingham (1730-1782) and included in Rudolf Erich Raspe’s ‘A descriptive catalogue of a general collection of ancient and modern engraved gems, cameos as well as intaglios: taken from the most celebrated cabinets in Europe…’ (1791).

If it survived until then, maybe it still exists today. Maybe a reader of this blog will recognise it. If you know where it is, please let me know.

Dr Juliet Carey, 12 September 2017

Useful links and further reading:

Read Power & Portraiture label and leaflet text

Watch Hilliard’s portraits ‘in greate’; a discovery?

Read ‘A radical new look at the greatest of Elizabethan artists’, Apollo online