What has Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire got to do with Albanian archaeology?

Discover why the Butrint Foundation's important archaeological record has come to be held at Waddesdon.

By Natasha Harlow, Butrint Research Associate

What, you might ask yourself, has Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire got to do with Albanian archaeology? It’s a fair question, and one I get asked quite frequently in my role as Butrint Research Associate.

Figure 1: group of loom weights (image: James Barclay-Brown/Butrint Foundation)

It all began back in the early 1990s when Lord Rothschild and Lord Sainsbury founded a charity (the Butrint Foundation) to preserve and protect archaeological remains of international importance at Butrint in southern Albania, just a stone’s throw across the Straits of Corfu from where they both enjoyed spending holiday time.

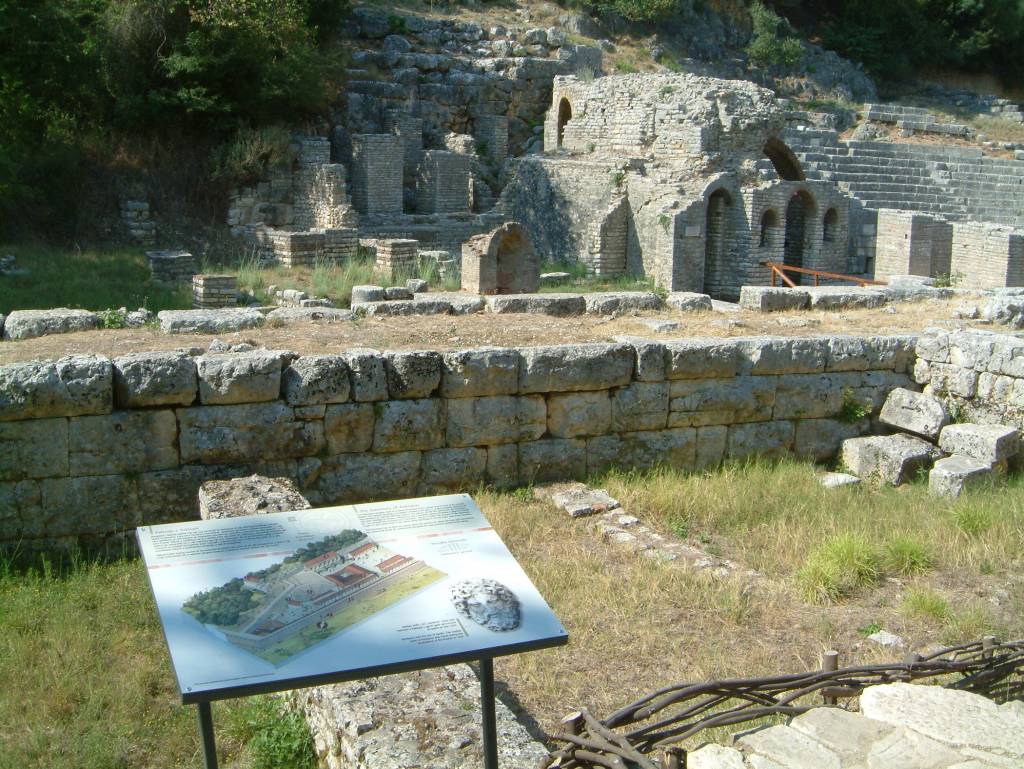

Butrint gained its UNESCO World Heritage Site designation in 1992. Its extensive heritage includes everything from Bronze Age remains to 20th century structures, with traces of the Roman and Byzantine city spreading across 200 hectares. The Butrint Foundation’s work over a 25 year period has resulted in a greater understanding of the site and its environs and special protection in the form of the Butrint National Park.

Important Roman buildings include the Forum, Theatre, a townhouse known as the Triconch Palace, and a major suburb of the Roman town located on the Vrina Plain in front of the walled city. The early Christian baptistery has a stunning mosaic floor depicting birds, fish and other animals. A Roman villa and Late Antique church were also excavated on the shore of Lake Butrint at Diaporit.

Hundreds of archaeologists have excavated at Butrint over the years, including teams from the University of East Anglia in Norwich and the Albanian Institute of Archaeology. Many Albanian students benefitted from the BF’s training programmes and have gone on to careers in archaeology themselves. Archive materials show the excavations of an Italian team in the 1920s and work carried out under the Communist government of Albania in the post-war period up to the 1980s.

While fieldwork by the Butrint Foundation has now finished, the post-excavation interpretation and publication programme continues, with 9 volumes already available. The artefacts uncovered during the digs remain in Albania, with displays at the on-site Butrint Museum housed in the Venetian fortress. However, the excavation archive, comprising paper and digital records, photographs, maps and plans, is housed at the Rothschild archive, Windmill Hill at Waddesdon Manor. Here, it is carefully being itemised, catalogued and repacked.

Working on the Butrint Archive is fascinating and rewarding. Every now and again, I come across an entertaining comment or note, such as the person who left us this message when producing a scale drawing of the aqueduct on the Vrina Plain: “Beware of angry Albanian sheep dogs. Listen to the skylarks. Ouch – prickly bushes”! It might not tell us much about the archaeology, but it gives us a glimpse into the world of being an archaeologist in Albania in the early 21st century. I hope one day to visit the site myself.