Visiting the Jewish gentry

Many National Trust properties have Jewish stories which have often been elusive. But now, Abigail Green explains, things have changed.

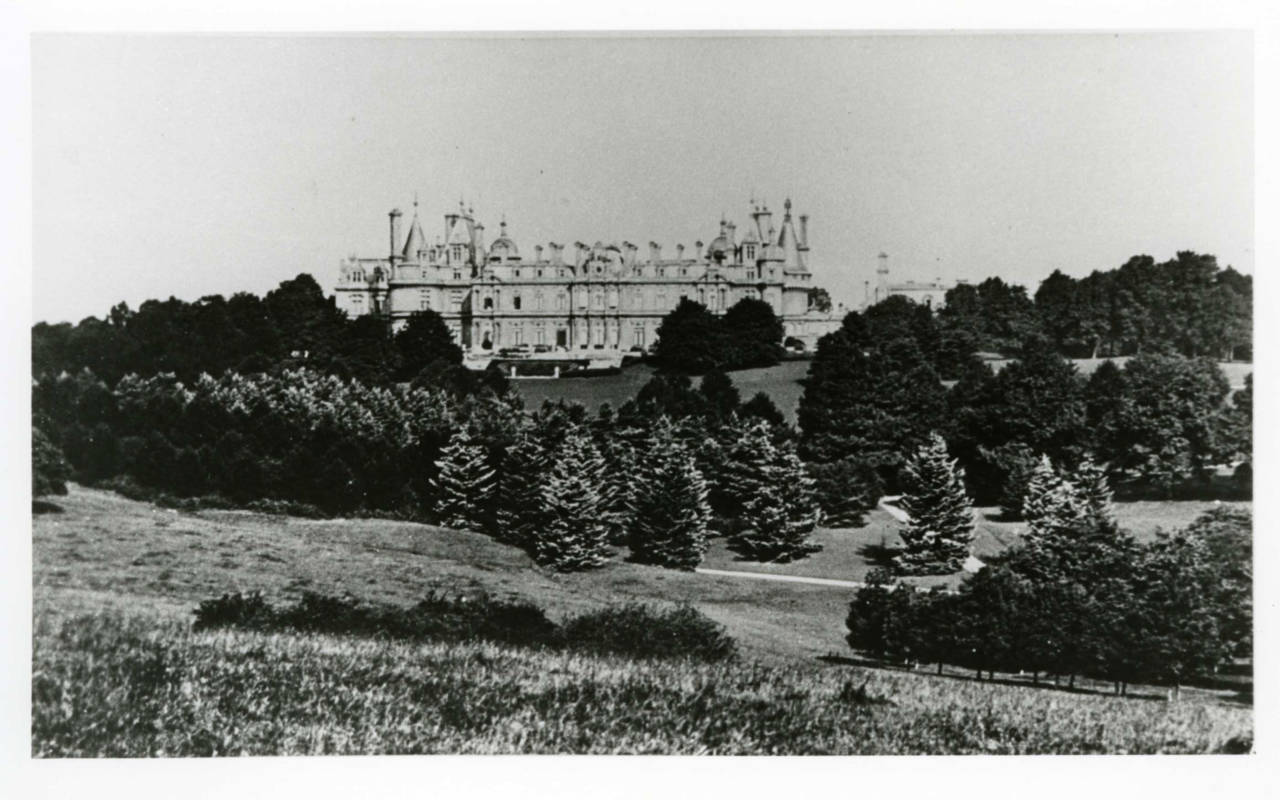

Back in 1957 when James de Rothschild bequeathed Waddesdon Manor to the National Trust, most of those involved in the acquisition regarded this neo-French Buckinghamshire château as “hideous”. Nor were its contents much more welcome.

“I hate French furniture,” Lord Esher, for the NT, informed James’ widow Dorothy. But the quality of this French furniture was quite exceptional. The Trust eventually agreed to take it all — with an unprecedentedly large endowment. Times change, and in 2018 Waddesdon (replete with its truly wonderful “French furniture”) is one of the National Trust’s most popular properties.

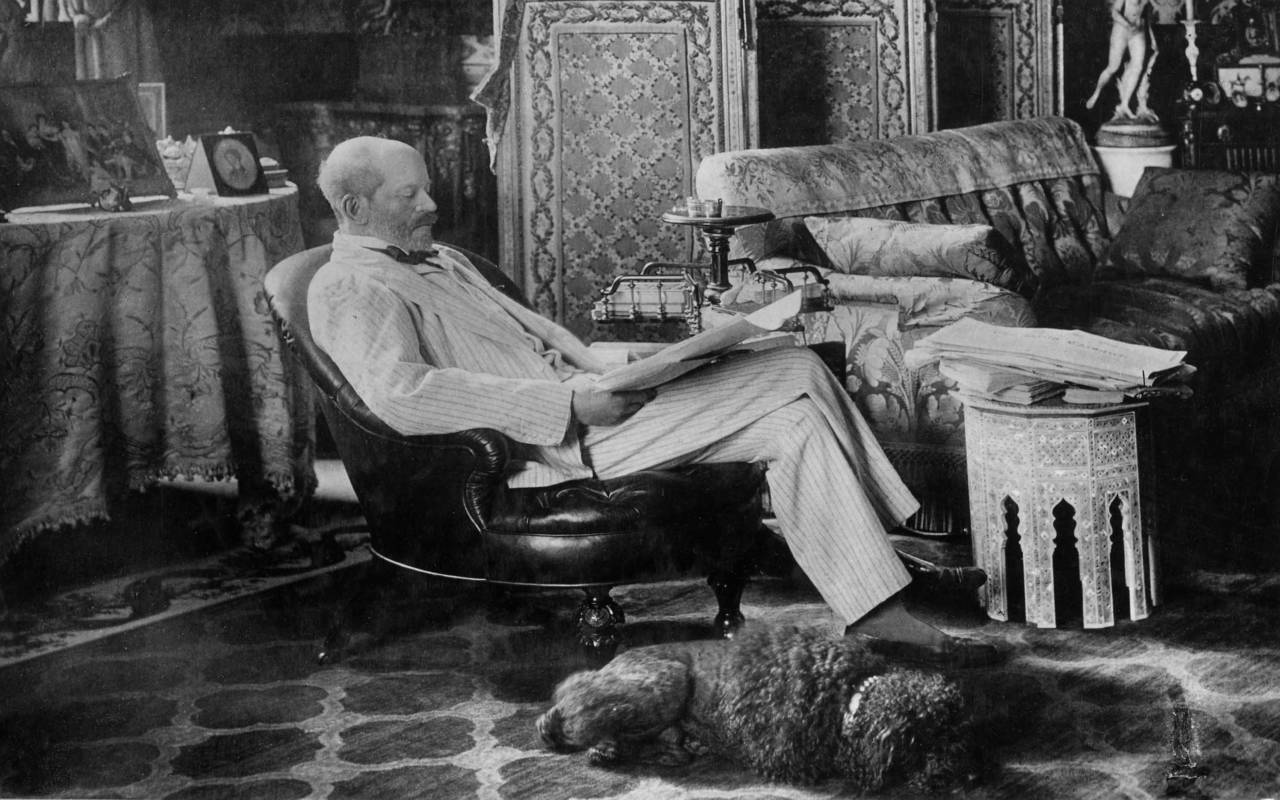

This September, for the first time, the Trust will be celebrating its Jewish heritage during the European Days of Jewish Culture. As Ferdinand de Rothschild was a leading figure in the Anglo-Jewish community, Waddesdon are amongst those taking part in celebrations. James and Dorothy de Rothschild were committed Zionists, and Waddesdon includes a room that commemorates the family’s role in obtaining the Balfour Declaration and support for the State of Israel over the years. For Waddesdon, the European Days of Jewish Culture provide an opportunity to explore this aspect of the family’s history, in greater depth: through special tours of the house, and through performances by Jewish storyteller Adele Moss, who will tell the legendary story of the family’s rise to riches in ways that connect with Jewish culture and folklore.

Visiting National Trust Jewish country homes reminds us that there were many different ways of being both Jewish and English. It expands our understanding of Jewish heritage because it shifts the focus from synagogues, cemeteries, immigrant quarters and places of communal belonging to sites of assimilation, social mobility and integration. At the same time, it reminds us of the diverse stories and hybrid identities that may be hidden behind a gothic house, a hunting box, and an English garden.

For the National Trust, participating in the European Days of Jewish Culture and Heritage is a first step towards engaging more profoundly with the Jewish heritage of its places. For readers of the JC, this new awareness of Jewish stories in sites so closely associated with Englishness is a happy indication of the more inclusive approach to national heritage we take in the 21st century.

By Abigail Green, written for the Jewish Chronicle.